March 13, 2025

Back to news

Carbon Watch

Key Points of Marginal Abatement Cost

It is worth noting that no MACC is stagnant; as the economy evolves, prices and supply chains shift, and new technologies arise, the MACC for a given firm or industry will shift as well. This is an added layer of complexity when some abatement decisions and investments must be made on long-time scales.

Marginal Abatement Costs and Cap-and-Trade Systems

Investors with a long-term focus in environmental commodity markets must reconcile the cost of abatement with policymakers’ objectives. Key questions to consider include:

The answers to these questions hold significant implications for investment decisions. Inconsistent, or incorrect assumptions about the cost of abatement, or unexpected shifts in policy, can lead to price volatility.

October 10, 2024

The Marginal Abatement Cost of Carbon

The cost of abatement, or the dollars required per ton of carbon to reduce greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions, is a key concept policymakers use when designing efficient environmental policies inclusive of carbon markets and carbon taxes. Because different sectors and firms face varying abatement costs depending on their technologies, energy sources, and operational needs, governments must create the right policies to incentivize cost-effective emissions reductions across the economy to meet long term decarbonization targets.

The Marginal Cost of Abatement (or “marginal cost”) refers to the cost of reducing the next additional GHG unit (typically a ton of CO2 or equivalent). It reflects the cost to a firm, industry, or economy of achieving an incremental reduction in emissions. This differs slightly from the Fundamental Abatement Cost, which represents the overall, or average, cost of reducing emissions to a specified level within a firm, industry, or economy over a specified period of time. The Marginal Cost of Abatement is a crucial concept for investors interested in environmental commodities as it provides necessary information for understanding the cost dynamics of emissions reduction strategies and optimizing investment.

Key Points of Marginal Abatement Cost

Marginal Abatement Costs Vary Across Firms & Sectors – Based on the technology, energy sources, and operational practices, different firms or sectors face diverse abatement costs. Industries that require significant upgrades of plants and equipment to decarbonize are likely to have higher marginal costs of abatement than others with more flexible or advanced technologies.

Increase Over Time – In most cases, marginal cost increases as a higher percentage of emissions within a particular sector or firm are reduced. This is because the cheaper and easier-to-implement measures (e.g. switching to energy efficient lighting) will initially reduce emissions at a relatively low cost, but more expensive technologies or fundamental changes in processes (e.g. investing in carbon capture technologies) will be necessary as deeper emissions cuts are required.

Used in Policy Design – Understanding the marginal cost across different firms and sectors is essential for policymakers to develop programs that incentivize cost-effective reductions. This also helps to explain why governments sometimes create multiple programs that target different sectors but are interconnected (see California’s program below).

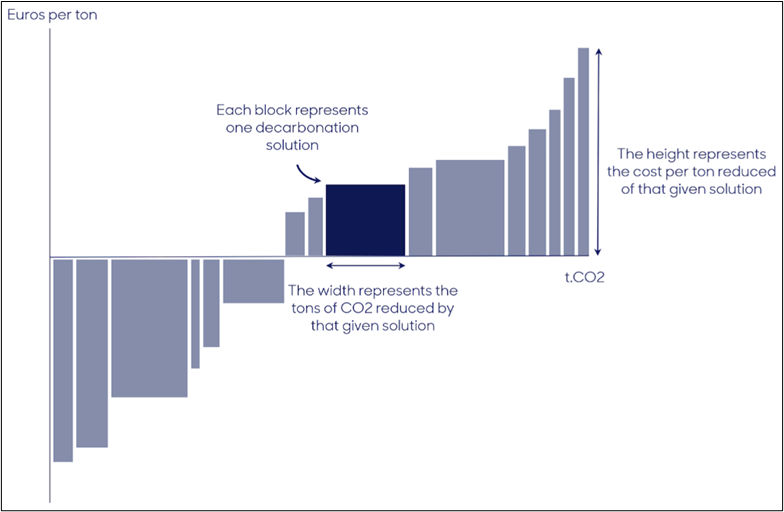

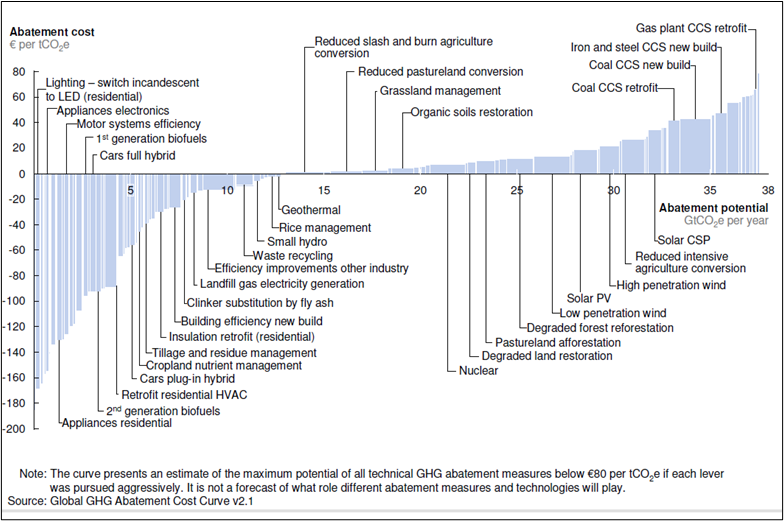

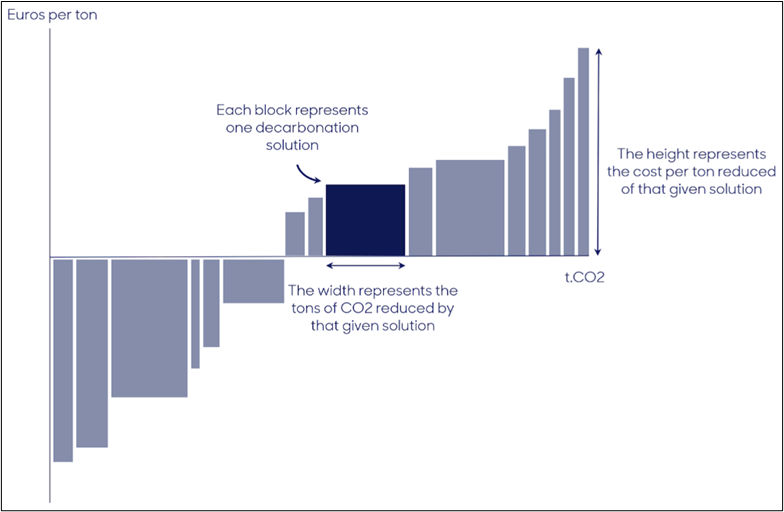

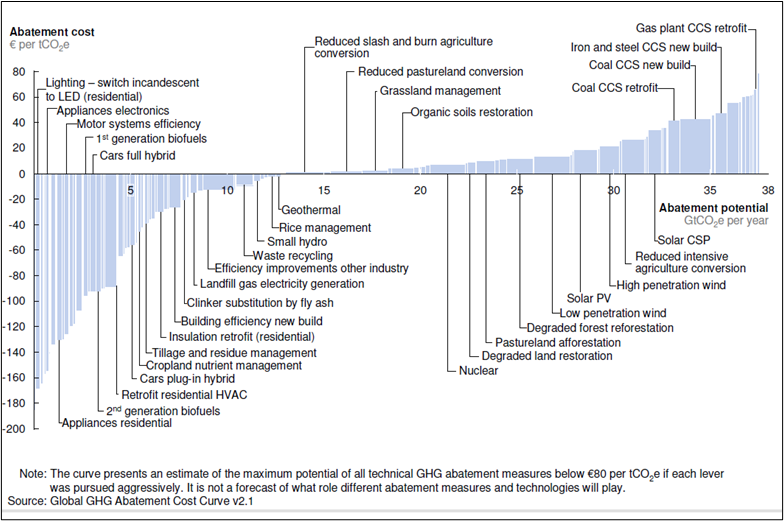

Marginal Abatement Cost Curves – For each stakeholder—a firm, industry, or economic sector—there are different combinations of technologies that could deliver the sought-after emissions cuts. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (“MACCs”) represent the cost to reduce emissions at different levels, helping to visualize which technologies or actions can reduce emissions at the lowest cost. Note that the solutions that are negative on the y axis of a MACC have a negative cost of abatement, meaning that there is an economic gain to reducing emissions via that solution. As various technologies have different abatement costs, MACCs help prioritize investments in the most relevant sectors to achieve emissions reduction targets. The two graphs that follow show the basic elements of a MACC, and an example of one of the most recognized abatement cost curves ever published:

Source: Homaio

Source: McKinsey & Company, Version 2.1 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve

Source: Homaio

Source: McKinsey & Company, Version 2.1 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve

It is worth noting that no MACC is stagnant; as the economy evolves, prices and supply chains shift, and new technologies arise, the MACC for a given firm or industry will shift as well. This is an added layer of complexity when some abatement decisions and investments must be made on long-time scales.

Marginal Abatement Costs and Cap-and-Trade Systems

In a cap-and-trade system, the marginal cost is expected to be reflected in the price of emission allowances (permits to pollute). As the cap on emissions becomes more stringent, firms need to either invest in emissions-reducing technologies or buy permits, potentially pushing up the price of allowances to correspond to the increasing marginal cost of abatement.

The price of a carbon allowance in a cap-and-trade program *should* reflect the marginal cost of abatement for obligated parties (emitters). If an emitter can reduce emissions for less than the current price of a carbon allowance, they will opt to do so. Conversely, if the cost to reduce emissions exceeds the price of an allowance, they will retire the allowance instead. However, due to permit banking, a liquid forward/futures market, and long-term project and cost management by emitters, the price of an allowance also theoretically reflects expectations about the future marginal costs of abatement an economy will face.

Policymakers must account for abatement costs when designing a cap-and-trade program. Once emissions targets are set, if price controls such as price caps are set too low emitters may be incentivized to delay climate action. If price controls are set too high, the program may cause potentially unnecessary economic burdens, most of which are often passed on to the public, undermining any political support.

To understand how important marginal cost of abatement is to cap-and-trade programs (and why it is a primary focus in ECP’s analysis of each market), we cite California’s Cap-and-Trade (“CCA”) program. The program’s regulator, the California Air Resources Board (“CARB”), addresses these issues in the 2022 Scoping Plan. The plan discusses abatement costs across various industries and highlights the complexity inherent in such analysis. Several key factors must be considered:

- Interconnected Measures: Policies that reduce emissions in one sector often have ripple effects on other sectors, sometimes in unpredictable ways.

- Long-Term Planning Horizons: Abatement often requires long-term investments, making marginal costs of abatement hard to estimate as they are dependent on a variety of unpredictable inputs such as interest rates and other hard-to-predict factors.

- Broader Economic and Societal Impact: CARB must weigh not only emissions reductions but also how policies impact California’s economy as a whole, which in turn further impacts abatement decisions.

- Feasibility and Flexibility: Technologies for abatement must be feasible and adaptable, yet what is considered feasible can evolve over time.

Investors with a long-term focus in environmental commodity markets must reconcile the cost of abatement with policymakers’ objectives. Key questions to consider include:

- What is the estimated relative marginal abatement cost in different industries under a cap-and-trade program? Are public plans from emitters aligned with these estimates?

- Where does CARB anticipate the majority of abatement will occur in the short and long run to meet climate targets, and are these assumptions realistic?

- How might policymakers and the regulator adjust the design of the program based on changes to this analysis in the future?

The answers to these questions hold significant implications for investment decisions. Inconsistent, or incorrect assumptions about the cost of abatement, or unexpected shifts in policy, can lead to price volatility.

Environmental commodity markets are complex because the scarcity of supply in cap-and-trade markets is driven specifically by policy, not by physical or economic limitations on the number of permits that can be produced. Because of this interaction between policy, market forces, project management, and technological advancement, it is essential for investors to maintain a dynamic understanding of both the cost of abatement and evolving regulatory frameworks. By keeping an eye on both the policy decisions of entities like CARB and the relative marginal abatement costs across industries, investors can better position themselves to capitalize on opportunities while managing risks.

For those investing in environmental commodities aligning investment strategies with both the marginal cost of abatement and anticipated policy shifts is one key to capturing value. This approach can not only provide financial returns but also contribute to meaningful progress toward global emissions reduction goals.