March 13, 2025

Back to news

Carbon Watch

There is a ballot initiative in this election cycle that may affect environmental markets much more directly than the presidential election. Voters in Washington State will have a decision to make on November 5 regarding their state’s cap-and-trade program. BI 2117, if approved, would repeal the Climate Commitment Act in Washington and prohibit the state from implementing any form of cap-and-trade or carbon tax program in the future. The ballot initiative is sponsored by Let’s Go Washington, a conservative Political Action Committee founded by hedge fund manager Brian Heywood that is sponsoring seven different ballot initiatives this year.

November 04, 2024

The U.S. Election Cycle and Carbon Markets

There is undoubtedly outsized attention on the upcoming U.S. presidential election; markets and industries across the globe await the outcome, and environmental commodity markets are no exception. For those involved in carbon and environmental markets, this presidential election could bring pivotal developments. However, historical precedent suggests the impact may not be as intuitive as one might expect. In fact, in some cases, recent presidential elections have had a counterintuitive effect on carbon markets.

For example, back in 2008 most carbon market participants expected newly elected President Barack Obama to prioritize the implementation of a federal carbon cap-and-trade market (likely through the guidance of the Waxman-Markey bill; for more information see this link). By the time Waxman-Markey was voted upon in the Senate, Obama’s political capital had been used up on healthcare and the 2008 Financial Crisis, leaving states to sort out cap-and-trade markets on their own.

By contrast, various stakeholders expected President Donald Trump’s election in 2016 to result in wholesale federal attacks on regional programs, which did occur primarily through the courts. Specifically, the Trump Administration challenged the constitutionality of California entering into an agreement with Quebec, seeing it as an international treaty with a foreign jurisdiction (which only Congress has the power to enter). However, these challenges stemming from his administration failed, and the response from a variety of state and regional programs was to bolster and, in some cases, extend them. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) went through a formal review that aggressively tightened its targets, while California’s Cap-and-Trade program (CCA) was extended through 2030.

While this election may seem more consequential than past presidential races, it is important to note that the executive branch will remain one of three branches of government, with limitations to its power over the states and their subsequent environmental programs. Neither candidate will have the power to directly affect or change these state programs via executive order, and any challenge to them would have to go through the court system (which is favorable to these programs as they have survived multiple challenges).

Below are our reasonable expectations on the divergent goals of a possible Harris or Trump Administration:

Political Winds: A Harris administration would likely seek to reinforce and harmonize state and federal climate policies, creating a favorable environment for the growth of carbon markets. One key area where we could see immediate action is in the reauthorization of California’s Clean Air Act waiver, which would embolden the state to set even more ambitious emission reduction goals and fuel standards. This move would not only strengthen the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) market but also encourage other states to implement similar standards, contributing to demand for low-carbon fuels and carbon offsets nationwide. Harris' administration might also strengthen carbon markets by offering federal tax incentives to companies participating in low-carbon fuel programs or investing in emission reduction initiatives. These incentives might include extending or expanding tax credits for carbon capture and storage (CCS), renewable energy projects, or green hydrogen production.

By contrast, a second Trump term could introduce legal and political headwinds aimed at constraining carbon markets. We might expect a Trump administration to use similar tactics from 2016 to attempt to weaken state autonomy over climate initiatives. A variety of legal challenges have been tried before without success.

Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): The previous Trump administration withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement in 2017 (which became effective in 2020). The Biden administration re-entered the Paris Agreement and strengthened the NDC to a 50-52% GHG reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. We would expect a second Trump administration to withdraw from the Paris Agreement again, while a Harris administration would remain with the status quo. The U.S. withdrawing for a second time (and crucially during the first global NDC commitment period 2025-2030) would likely have a negative impact on sentiment in global climate mitigation, although we would generally expect other countries to proceed with their Paris commitments.

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): The Biden Administration’s 2022 landmark clean energy and climate resilience legislation aims to reduce U.S. GHG levels to 40% below 2005 levels by 2030. A Harris administration would likely maintain and potentially strengthen the incentives under the IRA. A Trump administration would likely target specific provisions supporting imports (such as 30D for EVs) and renewable energy (like PTC 45Y or ITC 48E) for removal. However, incentives for oil, gas, and related investments like carbon capture and storage (e.g., 45Q) may remain intact.

For example, back in 2008 most carbon market participants expected newly elected President Barack Obama to prioritize the implementation of a federal carbon cap-and-trade market (likely through the guidance of the Waxman-Markey bill; for more information see this link). By the time Waxman-Markey was voted upon in the Senate, Obama’s political capital had been used up on healthcare and the 2008 Financial Crisis, leaving states to sort out cap-and-trade markets on their own.

By contrast, various stakeholders expected President Donald Trump’s election in 2016 to result in wholesale federal attacks on regional programs, which did occur primarily through the courts. Specifically, the Trump Administration challenged the constitutionality of California entering into an agreement with Quebec, seeing it as an international treaty with a foreign jurisdiction (which only Congress has the power to enter). However, these challenges stemming from his administration failed, and the response from a variety of state and regional programs was to bolster and, in some cases, extend them. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) went through a formal review that aggressively tightened its targets, while California’s Cap-and-Trade program (CCA) was extended through 2030.

While this election may seem more consequential than past presidential races, it is important to note that the executive branch will remain one of three branches of government, with limitations to its power over the states and their subsequent environmental programs. Neither candidate will have the power to directly affect or change these state programs via executive order, and any challenge to them would have to go through the court system (which is favorable to these programs as they have survived multiple challenges).

Below are our reasonable expectations on the divergent goals of a possible Harris or Trump Administration:

Political Winds: A Harris administration would likely seek to reinforce and harmonize state and federal climate policies, creating a favorable environment for the growth of carbon markets. One key area where we could see immediate action is in the reauthorization of California’s Clean Air Act waiver, which would embolden the state to set even more ambitious emission reduction goals and fuel standards. This move would not only strengthen the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) market but also encourage other states to implement similar standards, contributing to demand for low-carbon fuels and carbon offsets nationwide. Harris' administration might also strengthen carbon markets by offering federal tax incentives to companies participating in low-carbon fuel programs or investing in emission reduction initiatives. These incentives might include extending or expanding tax credits for carbon capture and storage (CCS), renewable energy projects, or green hydrogen production.

By contrast, a second Trump term could introduce legal and political headwinds aimed at constraining carbon markets. We might expect a Trump administration to use similar tactics from 2016 to attempt to weaken state autonomy over climate initiatives. A variety of legal challenges have been tried before without success.

Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): The previous Trump administration withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement in 2017 (which became effective in 2020). The Biden administration re-entered the Paris Agreement and strengthened the NDC to a 50-52% GHG reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. We would expect a second Trump administration to withdraw from the Paris Agreement again, while a Harris administration would remain with the status quo. The U.S. withdrawing for a second time (and crucially during the first global NDC commitment period 2025-2030) would likely have a negative impact on sentiment in global climate mitigation, although we would generally expect other countries to proceed with their Paris commitments.

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): The Biden Administration’s 2022 landmark clean energy and climate resilience legislation aims to reduce U.S. GHG levels to 40% below 2005 levels by 2030. A Harris administration would likely maintain and potentially strengthen the incentives under the IRA. A Trump administration would likely target specific provisions supporting imports (such as 30D for EVs) and renewable energy (like PTC 45Y or ITC 48E) for removal. However, incentives for oil, gas, and related investments like carbon capture and storage (e.g., 45Q) may remain intact.

Washington State Ballot Initiative 2117 (“BI 2117”)

There is a ballot initiative in this election cycle that may affect environmental markets much more directly than the presidential election. Voters in Washington State will have a decision to make on November 5 regarding their state’s cap-and-trade program. BI 2117, if approved, would repeal the Climate Commitment Act in Washington and prohibit the state from implementing any form of cap-and-trade or carbon tax program in the future. The ballot initiative is sponsored by Let’s Go Washington, a conservative Political Action Committee founded by hedge fund manager Brian Heywood that is sponsoring seven different ballot initiatives this year.

The Washington Cap-and-Invest (WCA) program is less than two years old, not yet through its first compliance period (2023-2026). If BI 2117 is approved, it is expected that allowances under the program, which currently trade near $50 in the secondary market, would effectively be worthless. Prices were well below $40 for most of the year, with three consecutive auctions clearing below $30. By contrast, allowances were in the $50-$55 range for most of 2023 and into 2024 ahead of BI 2117 making the news.

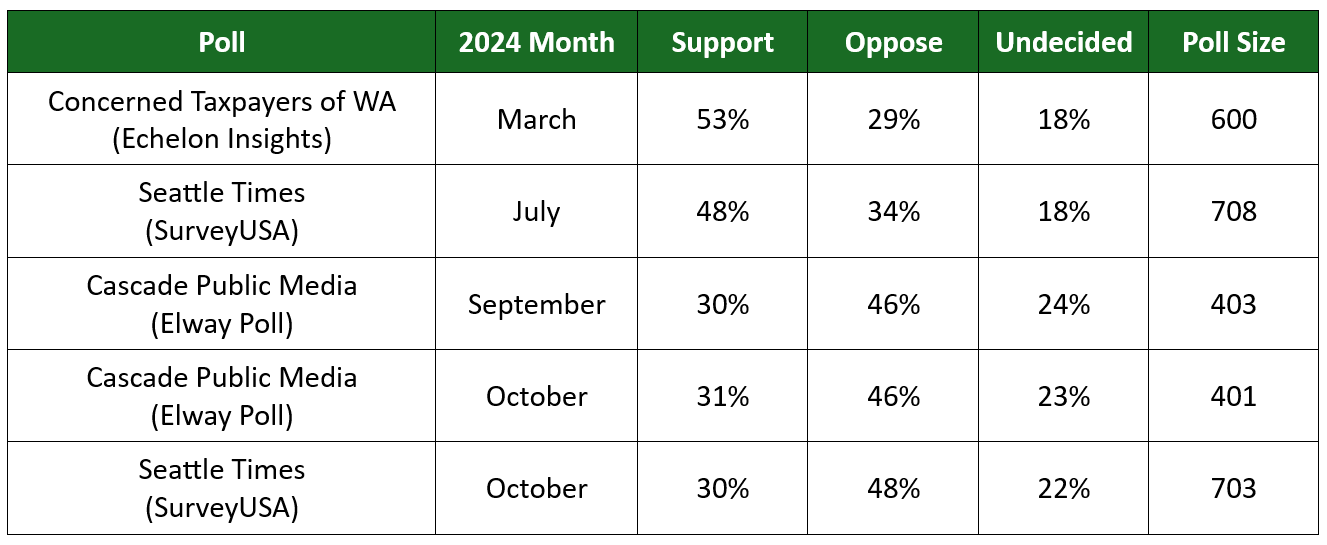

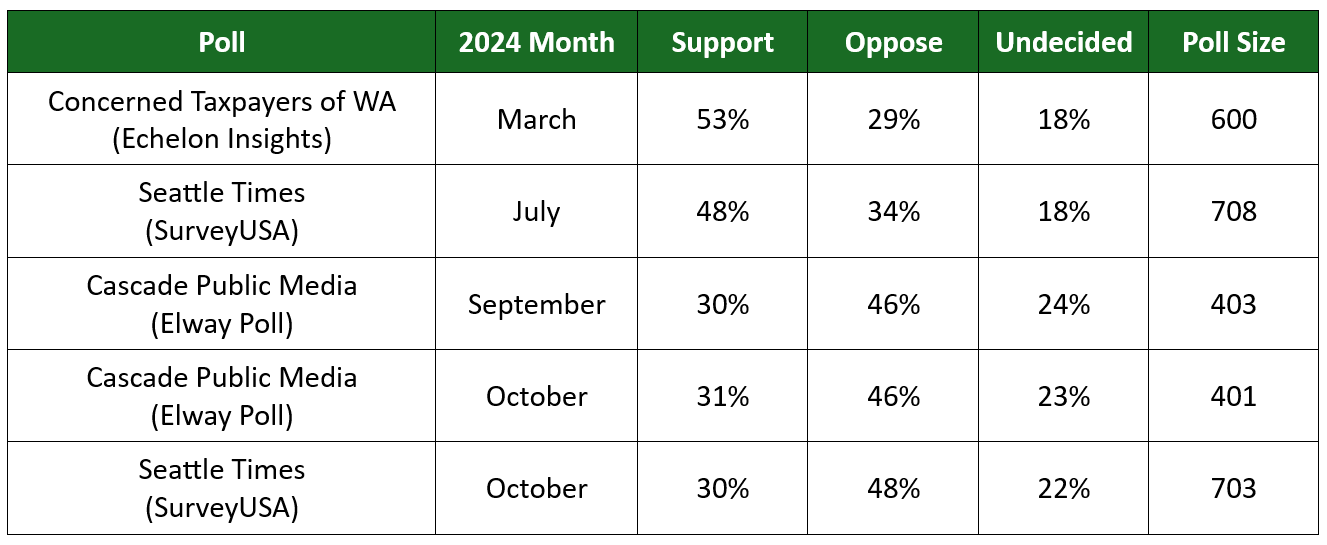

While both the opposition and supporters of the initiative have raised similar amounts to bolster their cause (over $15 million as of this publication, according to Ballotpedia), a sample of public polling on the issue over times shows a shift in voter preferences towards the opposition:

Again, if historical precedent is an indicator, this ballot initiative is similar to California’s Proposition 23 back in 2010, which would have suspended implementation of AB32 (California’s initial climate law) until California’s unemployment rate dropped to 5.5% or less for 4 consecutive quarters. The ballot proposition was defeated by a 23% margin despite the state unemployment rate at the time being ~12%.

ECP will monitor the results of BI 2117 closely.

Again, if historical precedent is an indicator, this ballot initiative is similar to California’s Proposition 23 back in 2010, which would have suspended implementation of AB32 (California’s initial climate law) until California’s unemployment rate dropped to 5.5% or less for 4 consecutive quarters. The ballot proposition was defeated by a 23% margin despite the state unemployment rate at the time being ~12%.

ECP will monitor the results of BI 2117 closely.